Animal Cancer Care and Research Center exceeds expectations in its first two years

As research hummed in 2020 at Virginia Tech's biomedical center during the COVID-19 pandemic, a clinic nearby was opening on the front lines of a battle against another dreaded C-word, granting hope both for beleaguered pet owners today and cancer patients – animal and human – in the future.

The Animal Cancer Care and Research Center recently celebrated two years since its opening in Roanoke beside Virginia Tech’s Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC (FBRI).

“Despite having opened during the pandemic, the veterinary clinical oncology service is exactly where we’d expected to be in regards to case load and clinical reputation,” said Margie Lee, interim director of the cancer center.

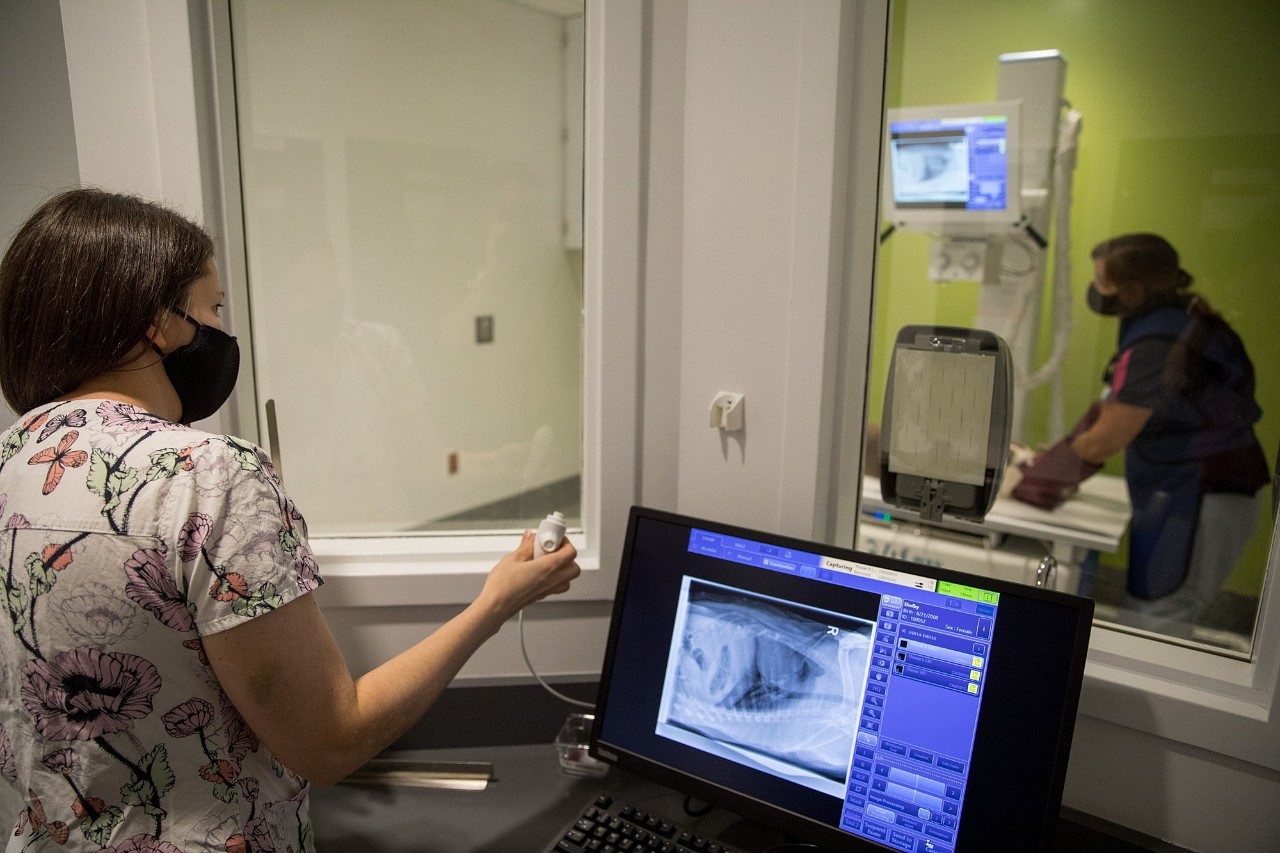

In 2021, the 18,680-square-foot center treated 2,188 dogs and 333 cats, all referred by veterinarians. There are currently 62 dogs enrolled in experimental clinical trials free of charge to the pet owner.

“We provided over $100,000 in financial assistance for the treatment of animals and received $250,000 in research grants,” said the cancer center’s administrator, Dan Vruink. “We have become a trusted partner for veterinarians in the region for veterinary oncologic advice.”

But it is cancer research that is drawing national attention to the Roanoke-based center.

“Our research program has already exceeded expectations,” Lee said. “We have dozens of cancer clinical trials for pets running ahead of schedule, and through collaborations with the FBRI and College of Engineering, we have custom-built equipment for creating new ways for tumor ablation.”

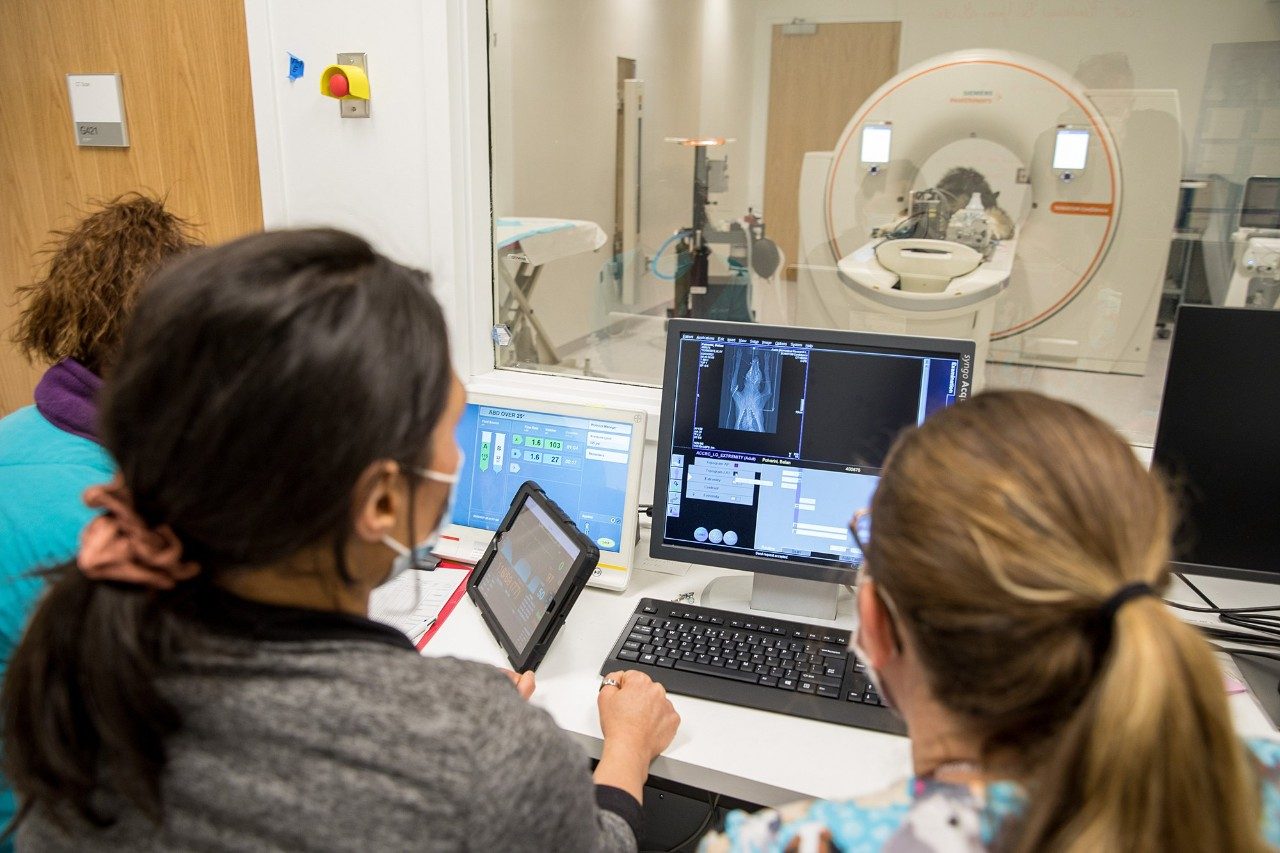

The clinic, one of three hospitals within the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, was recently featured in a Nature journal article linking the study and treatment of cancer in dogs to similar forms of the disease occurring in human patients.

While offering more traditional medical oncology such as chemotherapy and partnering with the Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Blacksburg for surgical options, the cancer center has established itself as the only site in the region offering radiation therapy for pets with cancer.

At the center, “we are using high intensity focused ultrasound waves, or high-frequency electrical fields, to destroy cancerous tissues,” said Nikolas Dervisis, veterinary medical oncologist. “These approaches open avenues for killing tumors on an outpatient basis and study the effect of the tumor cell kill into mobilizing the patient's immune system against the cancer.”

The centerpiece of this approach is a $3.23 million linear accelerator that meets specifications for human use but is employed solely for use in animals.

"This advanced technological system is specifically designed for tumor ablation. We are capable of treating cancerous tissues with radiation anywhere in the body with high precision and submillimeter accuracy,” said Ilektra Athanasiadi, radiation oncologist.

Going into a third year, Vruink’s expectations are simple: “More research, more cases, and more hope to families of pets with cancer.”

Of course, not every cancer case treated in companion animals results in a successful recovery, but the center offers hope to pet owners where there is often very little through traditional veterinary care.

Furthermore, research conducted on cancer in dogs and cats not only offers hope for better treatment of pets in the future, but people, also.

“Our researchers are already funded by the National Institutes of Health to develop preclinical data for how these treatments may work for humans,” Lee said. “We are very hopeful that these findings can translate to human medical trials.”

In the Nature article, veterinary oncologist Joanne Tuohy of the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine noted how the shared environment of human and canine patients is central to the translational cancer studies , while veterinary neurologist John Rossmeisl of the veterinary college told Nature the “molecular, genetic, clinical similarities of canine and human brain tumors is pretty remarkable.”

Roanoke became a natural choice for the location of the cancer center, Lee said, because “the population and location would support animal clinical trials with research collaborations among the medical researchers.” The center’s proximity to the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC is advantageous for research collaboration and for the sharing of some technical equipment.

Lee said the research that could benefit both animals and people, and the close collaboration between various colleges and departments is important in bolstering Virginia Tech as a leader in One Health, connecting human, animal and environmental health.

“Translational research is when you can move research from the laboratory to the clinic and that includes cancer treatment as well as better cancer diagnostics,” Lee said. “For our purpose it includes collaborations with engineers, physicists, immunologists, physiologists, and medical specialists such as our veterinary oncologists to develop innovative and unique devices that can better target tumors.

“This approach to One Health is likely to position Virginia Tech as a leader in novel cancer treatments.”