Advanced algorithm aims to optimize cattle feeding

The calculations could save farmers money and reduce environmental impact, say Virginia Tech researchers.

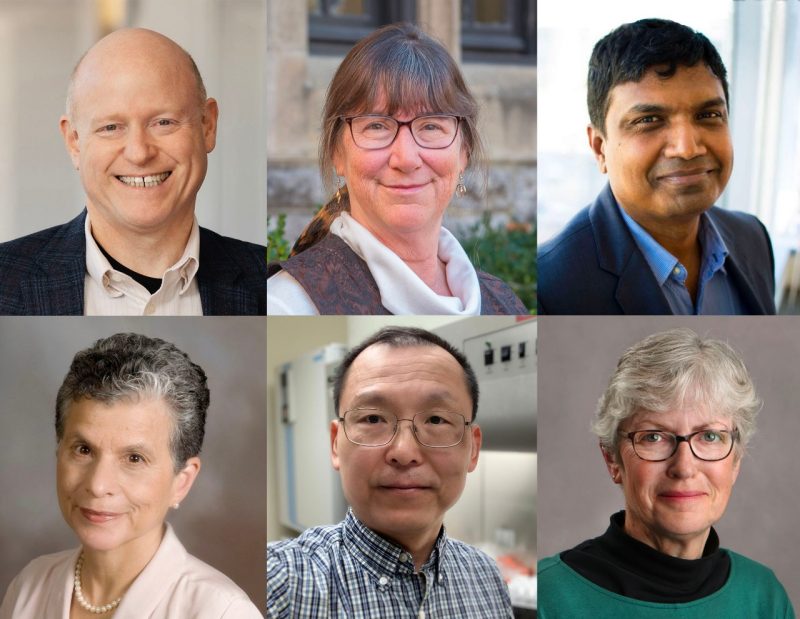

“With the advancement of technology, our idea was that we now could tailor the feedings to the individual cow instead of the average population,” said Mark Hanigan. Photo by Sam Dean for Virginia Tech.

To help combat burgeoning costs for producers, Virginia Tech researchers are creating advanced computer algorithms and models to optimize cattle feedings.

Currently, dairy cattle are kept in different pens based on production and are fed according to those specific populations. But even within those pens, some cows are genetically inferior and require additional nutrients, such as protein, and others will require less than average. The economic impact of these variances is estimated to be between $2 billion and $10 billion yearly in the United States.

The goal of this research is to deploy a self-learning control and diagnostic system that can identify cows with health or production problems, control feeding at the milking robots to generate individualized diets, optimize diets for each cow in the entire herd, and to discover individual animal requirements for multiple nutrients.

“With the advancement of technology, our idea was that we now could tailor the feedings to the individual cow instead of the average population,” said Mark Hanigan, the David R. and Margaret Lincicome Professor of Agriculture in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences’ School of Animal Sciences and a fellow in the Center for Advanced Innovation in Agriculture. “With our algorithm, we can feed each cow to their true requirements, and we should save money on at least half of the cows by not overfeeding them.”

Additionally, cows that are being underfed protein and other nutrients could produce better with these individually tailored feedings.

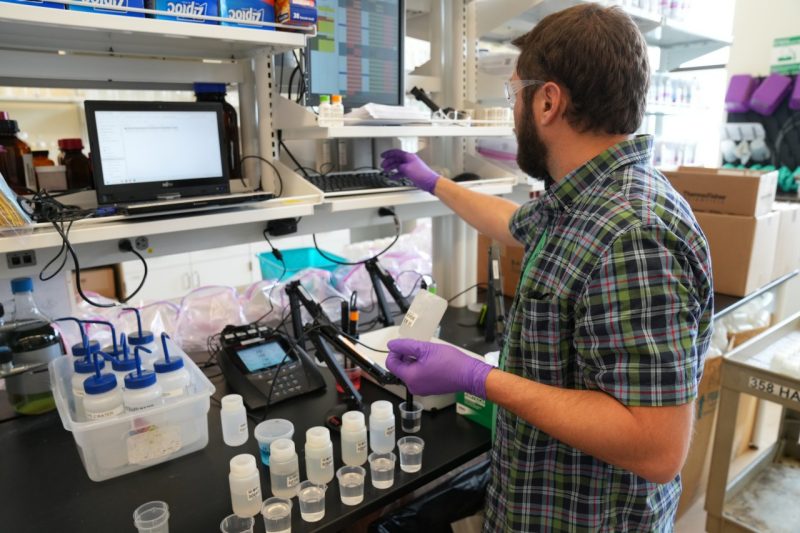

Robotic milking systems, along with other automated feeders, are being installed on farms and at production facilities. The advent of these feeders presents the opportunity to use an advanced feeding system to feed individual animals and work to assess individual animal response variation to protein and amino acid supplies had not previously been conducted in dairy cattle, according to Hanigan.

A bonus to using these innovative algorithms is that by optimizing cattle nutritional intake, it also could also the animal’s excretion of nitrogen, potentially reducing emissions and environmental impact.

The researchers, including graduate students Leticia Marra Campos in the School of Animal Sciences, Hayden Ringer in the Department of Mathematics, and Sonal Jha in Synergistic Environments for Experimental Computing, will do field work at Hillside Farm in Dublin, Virginia. The production facility is operated by multiple generations of Hokies, including Scott and Laura Flory ’08.

The work is being done in partnership with the College of Engineering’s Department of Computer Science, where faculty are assisting with the software development and the aggregation of various data collection systems.

The collaboration doesn’t stop there.

An additional partner on the research is the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture’s Department of Animal Science. Other campus partners include the College of Science’s Department of Math, which is helping with the diet optimization algorithm. The computer science department also is assisting the School of Animal Science with anomaly detection.

“We’re starting to phenotype these cows,” Hanigan said. “We’re working with a couple geneticists because our plan is for this project to run for at least a decade and collect information on hundreds of thousands of cows so we can develop breeding values for nutrient efficiencies that are used in the industry.”