Fresh Perspective

A MIX OF BLUSTERY WINTER WEATHER AND SPRING WARMTH GREETED A MONUMENTAL GATHERING AT THE SMITHFIELD PLANTATION IN MARCH.

As snow squalls and sunshine battled for territory in the sky, descendants of people once similarly at odds came together on the ground for a ceremony at the remains of the historic Merry Tree.

“You can make the assumption that our ancestors gathered very much in the same way, less the speakers and automobiles,” said Kerri Moseley-Hobbs, whose four-times-great-grandfather Thomas Fraction was once enslaved at Smithfield. “When we’ve been trying to do something today, the clouds break and the sun comes out, so we were joking around that the separate ancestors are up there fighting, and when we need to do something, they get real aggressive and break up the clouds.”

Moseley-Hobbs was joined at the tree by about 100 descendants of people once enslaved at Smithfield. The Merry Tree, which is also called the Merry Oak, is believed to have been a sacred gathering place for their ancestors. was claimed by a storm in 2020, its crown has been removed and is in the process of being converted into two art installations, which are expected to be unveiled later this year.

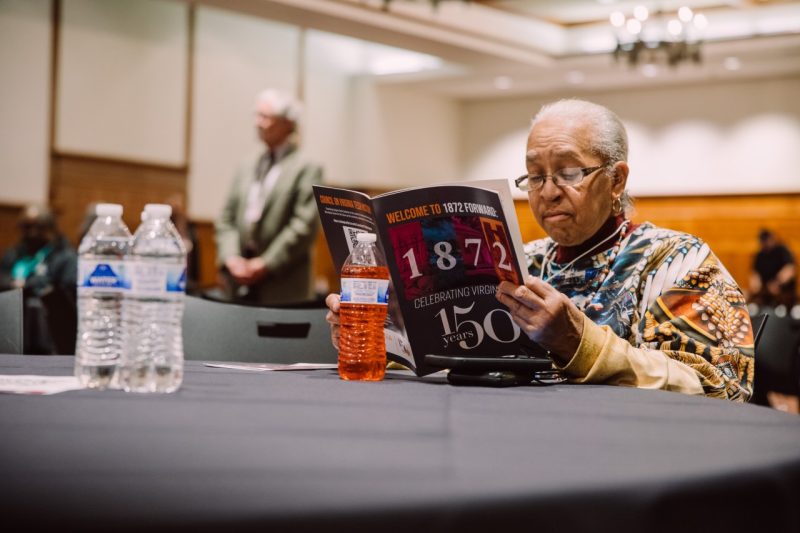

The ceremony was part of 1872 Forward: Celebrating Virginia Tech, a multiday event in March that recognized the diverse groups who helped shape the university: Indigenous people, African Americans, and European settlers.

The event, a homecoming of sorts, offered opportunities for reflection as well as music, dancing, and fellowship—experiences unique to this moment in time. Throughout the weekend, descendants were joined by representatives from the Monacan Nation, the land’s original caretakers, and members of the Preston family, whose ancestors built the Williamsburg-style home on the slave plantation in 1774. (Read the poem written and performed by Menah Pratt-Clarke during the celebration.)

The diverse gathering marked a seminal moment for the Council on Virginia Tech History, which organized the weekend event as part of the university’s yearlong Sesquicentennial Celebration. In addition to the Merry Tree ceremony, 1872 Forward included activities that ranged from launching multiple books and unveiling designs for new campus historical markers to a cultural arts celebration and a multifaceted conversation exploring the complex history of the geographic spaces now occupied by Virginia Tech.

“In a way, this can be the world in miniature, I suppose,” said Brokie Lamb, a descendant of the Preston family who took part in the conversation. “I grew up, as many white people do, in a sort of de facto segregated world, and when we’re living in separate worlds, I worry we lose the ability to talk to each other. I hope that gets better, and I think being more inclusive in places like this and telling a more complete and accurate story is a way to do that—the first steps in doing that, anyway.”

In 2017, as Virginia Tech began planning for its sesquicentennial, President Tim Sands identified the milestone celebration as an opportunity to compile and share a comprehensive history of the university in the context of the present and the Beyond Boundaries vision for the future.

“The thought was it might be appropriate to have a body on campus that starts to think about Virginia Tech history and to think about how we’re telling that history as we look toward the future,” said Menah Pratt-Clarke, vice president for strategic affairs and diversity.

The Council on Virginia Tech History, a 25-person group spanning a breadth of academic disciplines and personal interests, was established to not only collect those stories, but to develop opportunities to meaningfully engage people with them. In an effort to illuminate the Beyond Boundaries vision for the future, the council would specifically seek to give voice to previously untold stories and relate complicated histories in their full context by lifting up carefully researched and authenticated sources.

Bob Leonard, a professor in the School of Performing Arts, was selected as the group’s chair. Leonard’s background includes work with the Montgomery County-based Dialogue on Race as well as dialogue creation and community-building through theater arts.

Leonard said the council’s first goal was to sharpen a carefully considered mission and chart a direction for concrete actions.

“That resulted in pretty unanimous consensus that we needed to gather as many perspectives as possible and then share them using multiple methods within the context of, ‘We want to hear more stories.’ Not that, ‘This is the story,’” Leonard said.

During the months and years that followed, six projects emerged, six committees formed, and dozens of people with connections to the university and region began bringing the work to life.

Some of the projects expanded on existing efforts such as the VT Stories initiative that debuted in 2015. (See a related story from the winter 2016-17 edition of Virginia Tech Magazine.)

For Virginia Tech’s 125th anniversary, History Professor Peter Wallenstein researched and wrote “Virginia Tech, Land-Grant University, 1872-1997.” For the university’s sesquicentennial, Wallenstein is preparing a second edition, as well as publishing a new book that will revisit the full history of Virginia Tech and its people. Wallenstein’s research has served as a key resource to the Council on Virginia Tech History.

Other projects focused on new paths for presenting university history, such as campus historical markers, public art installations, and Voices in the Stone, which supports live performances, utilizing theater, dance, and music to bring history to life.

Visualizing Virginia Tech History is a council project with a particularly multidisciplinary approach to elevating the university’s history. A group of almost 30 faculty and students spanning numerous university disciplines have utilized creative technologies—including projection mapping, augmented reality, and 360-degree videos—to not only tell history, but to allow users to experience it. To date, the group has developed digital history exhibits, a virtual 360 tour of Solitude, and an augmented reality walking tour of the Blacksburg campus.

The council is planning several events to showcase its work in the fall, including a public art unveiling, the release of Wallenstein's updated book, and the dedication of Vaughn-Oliver Plaza, a tribute to the family of the first Black employee (Read a related story.)

In addition to project development, the council led the way on recommending new names for two residence halls whose previous names were inconsistent with the rich heritage and increasingly diverse community that is Virginia Tech today.

In 2020, Hoge Hall was named for Janie and William Hoge, an elderly Black couple who housed the first eight Black students at Virginia Tech. At the time, university guidelines required students of color to live off-campus. Whitehurst Hall was named for James Leslie Whitehurst Jr. ’63, the first Black student to secure on-campus housing. He later became the first Black member of the university’s Board of Visitors.

According to Pratt-Clarke, renaming the buildings represented an important moment for the council’s work. Although the name changes had been debated previously, it was the extensive research and recommendations of the council that ultimately helped move the change forward.

Another key aspect of the council’s work has involved cultivating relationships with descendants of the families once enslaved on and around the area in Blacksburg the university now occupies and with the descendants of the region’s Indigenous people who were the original custodians of the land. Those relationships helped inform the direction of the council, especially related to these often underrepresented aspects of the past.

“What will be our relationship with our past involving enslavement, what does that piece look like?” Pratt-Clarke said. “And we’ve long had this relationship in some way or another with the Monacan people, but how do we honor that?”

The former would be greatly advanced by the development of a partnership with the More Than a Fraction Foundation and its founder, Moseley-Hobbs, who also served as a consultant to the council. Moseley-Hobbs first reached out to the university in 2016 to learn more about her relative Thomas Fraction. Since then, she’s become a staple at events related to Smithfield and Solitude and has established the foundation, which co-sponsored 1872 Forward.

One of the highlights of the weekend was Contested Spaces: A Tri-Racial Conversation. The special discussion, moderated by Moseley-Hobbs, brought together representatives from the Monacan Nation, the Preston family, descendants of people once enslaved at Smithfield, and the present-day lineage of residents of Wake Forest, a community established by post-Civil War freedmen who had been enslaved on what is now Kentland Farm.

Members of Native American communities, including Monacan Chief Kenneth Branham, also played an integral role in 1872 Forward. Branham offered remarks honoring the university’s connection to Native American land.

“Virginia Tech has always had a pretty good relationship, compared to a lot of colleges, when it comes to the Monacan,” said Branham, citing university faculty who had long visited their tribal home on Bear Mountain in Amherst County. “I want to thank Virginia Tech for putting an institution like this on our land.”

“The revelation of the Monacan Nation and the Fraction family having a direct connection to the founding of Virginia Tech was new information for me,” said event attendee Marguerite Harper Scott ‘70. Harper Scott, who was one of the first Black women to enroll at Virginia Tech, is a member of the Cornerstone Alumni Advisory Board. “The transparency of the history that was shared makes me hopeful for the future. It is important to know how institutions were formed. I love that my university is embracing the truth.”

For Ronnie Spellman ’95, hearing the stories the Council on Virginia Tech History helped bring to light provided additional context for a topic he loves to discuss.

“I’ve always loved to talk about Virginia Tech history,” said Spellman, who made history himself as the first Black president of the Student Government Association. “And I knew some of it. Now that I have more of it, I realize it’s been an incredible evolution.”

Spellman, a member of the Student Affairs Alumni Advisory Board, said learning about the past helps him more fully appreciate the work that inspired the progress the university has made from its founding to the present.

“I look at the university today, we’ve evolved, and we continue to grow and evolve, but we can’t have the Virginia Tech of today without having the Virginia Tech that we’ve had for the past 150 years,” he said.

Leonard said seeing the council’s work successfully displayed in such public, multiday and multivenue events was a joy.

“It was exciting as all get-out,” Leonard said. “It was all so high energy and working with a fantastic team of people having to make decisions on the fly. … The dramatic impact of these events was especially gratifying for this old theater dog.”

Pratt-Clarke said as she’s reflected on the weekend and the ongoing work of the council, she realized just how critical the vision and support of Virginia Tech’s leadership has been to their success.

“This would not have happened without President Sands’ leadership and commitment,” she said. “The work of the council took a lot of time and effort from a lot of people, and he championed it at every stage—from creating the council to ensuring there was a budget. He’s been a visible champion for inclusion and diversity and the understanding of the importance of connecting the past, even if it’s complicated and filled with pain and oppression, to the present and future of Virginia Tech.”

That future will undoubtedly involve more work for the Council on Virginia Tech History—work to discover, explore, research, and share as the university continues to stride forward.

“It’s a living project because we’re making history every day,” Leonard said.

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)