Degrees created opportunity for alumnus to become a global expert in seafood traceability

The “applied economics toolbox” Miller gained at Virginia Tech has helped the seafood industry overcome its challenges, especially during Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Alexander Miller ’06 B.S. fisheries science, ’06 B.S. environmental policy and planning, ’09 M.S. agricultural and applied economics. Photo courtesy of Sara Miller.

Alexander Miller’s journey toward becoming a global expert in seafood traceability began at an early age with participation in the Virginia Junior Academy of Science and enrollment in the Chesapeake Bay Governor's School. Miller '06, M.S. '09 was working on building an aquaponics system during his senior year of high school.

“I needed a tank to build the system, and Walter Adey, a research scientist at Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, had recently donated a production tank that I ultimately used. My agriculture teacher thought I needed permission to use the tank, so I reached out to Walter, and the rest is history,” Miller said.

Through conversations, Miller discovered that Adey was going to the subarctic to start his research and needed someone to care for his property and aquariums, which used a technology that he had invented called an algal turf scrubber. Miller was the perfect person for the job.

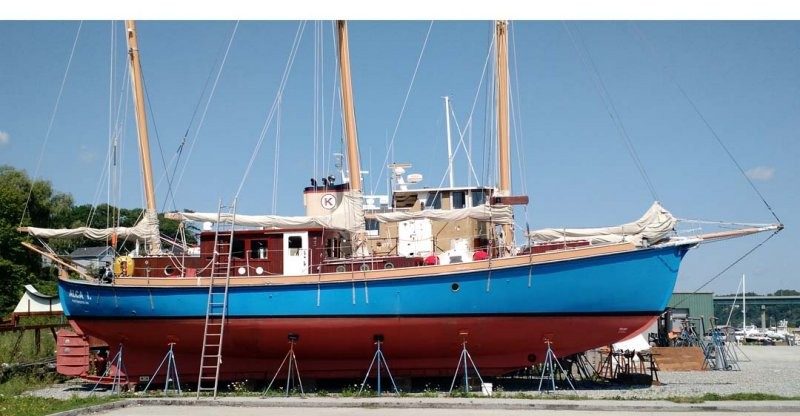

Over many summers and holidays, Miller took care of the property and helped Adey build a three-masted schooner. As the schooner was being built, Miller also got certified to scuba dive and did so for the Smithsonian for many years.

A three-masted schooner

In 2002, Miller enrolled at Virginia Tech to study fisheries science, now called fish conservation, in the College of Natural Resources and Environment. In summer 2003, he got to sail on the very boat he helped build, the schooner ALCA i.

Miller and Adey sailed to the subarctic, primarily diving and working around the Canadian Maritimes studying the biogeography of marine macroalgae or seaweed. Miller quickly saw the socioeconomic impact the collapse of the cod fishery had on the region. While Miller was working more with marine biology at the time, he recognized that the collapse of the cod fishery wasn’t only a biological problem, but also a policy and economic problem. This realization led him to immediately return to Virginia Tech to pursue a second degree in policy and planning.

After Miller’s second degree, he still felt that he needed a way to tie together his biology and policy knowledge. He had taken some economic classes with Kurt Stephenson, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, who subsequently had an oyster aquaculture project he was getting ready to start. This project was the perfect way to introduce economics into his biology and policy knowledge, and the natural step was to begin working toward his Master of Science in agricultural and applied economics.

Natural and human-made disasters

Completing his master's degree was the springboard to Miller’s first full-time job. After graduate school, Miller headed for the Gulf Coast, which three years before had been devastated by Hurricane Katrina, a Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage. Congress had recently allocated millions of dollars and needed an economist to study economics, collect economic data, and create economic models to help the seafood industry recover. Miller was hired as the staff economist for the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission to fulfill this role.

Miller said that his master’s degree gave him an “applied economics toolbox” with which to help the seafood industry overcome its challenges after Hurricane Katrina.

On April 20, 2010, the toolbox came into play again. The oil drilling rig Deepwater Horizon, operating in the Macondo Prospect in the Gulf of Mexico, exploded and sank, causing the largest spill of oil in the history of marine oil drilling operations. Four million barrels of oil flowed from the damaged Macondo well over 87 days, before it was finally capped on July 15, 2010.

Miller raised his hand to provide leadership and direction to help the seafood industry recover in the wake of this disaster. Miller’s work included seafood marketing, traceability, sustainability, and testing, as well as other economic development activities. During this time, seafood traceability was up and coming, and Miller’s knowledge helped him become known as an expert in this field.

After leaving the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission, Miller took his experiences from the Gulf Coast and joined Trace Register, a market-leading electronic traceability company used by the global seafood industry in over 50 countries to achieve full-chain traceability. Miller served as vice president of business development, further developing the value proposition of electronic traceability.

Today, Miller works for NOAA Fisheries as a trade monitoring program manager.

He provides seafood trade monitoring, traceability, technology, business, and international trade expertise and leadership for NOAA Fisheries’ Trade Monitoring Programs, facilitating approximately $12 billion of annual seafood trade. Miller identifies and operationalizes emerging technological opportunities, including guiding the development of NOAA’s International Trade Data System, Trade Monitoring System, Global Seafood Data System, and Seafood Import and Export Tool.

The perfect triangle

The Gloucester, Virginia, native said his degrees gave him this perfect triangle of biology, policy, and economics.

Looking back on his time as a student at Virginia Tech, Miller values the friendships he made, especially those with his international classmates. The exposure to different cultures and experiences has been beneficial to the international work that he now does.

As for advice to students today, Miller cited a quote from Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple: “You can't connect the dots looking forward, you can only connect them looking backward. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.”

Referring to his career, Miller said, “You never know where the ‘dots’ will take you and how they will connect, so always keep an open mind.”

Written by Melissa Vidmar