From the Blue Ridge to Antarctica and beyond: How a Virginia Tech and 4-H alumnus found his way to National Geographic

As a photographer, videographer, and explorer for 25 years, Chris Kugelman ’94 has worked on a multitude of awe-inspiring projects, including the Disney+ series “Welcome to Earth” starring Will Smith.

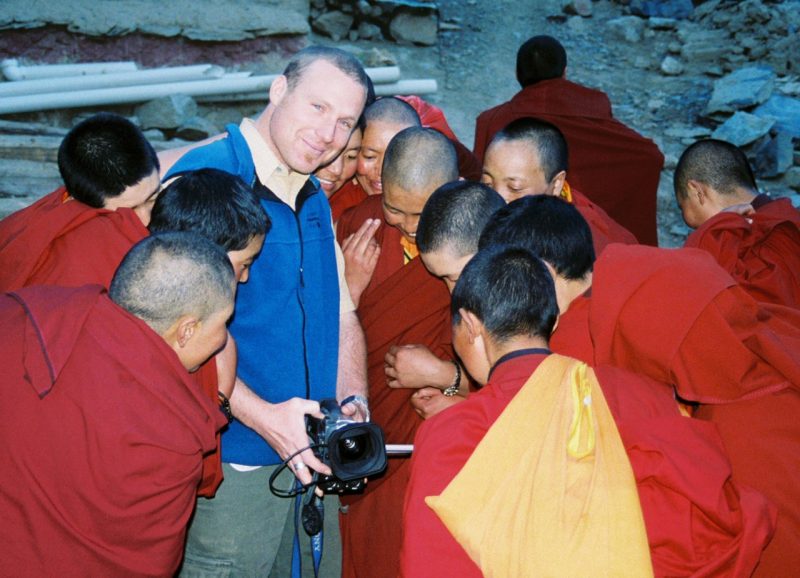

With a love of the outdoors and his first photography class he took as a 4-Her, Chris Kugelman '94, center, found his way from Blacksburg to National Geographic with stops across the globe including Antartica, New Zealand, and Nepal in his 25 year career. Photo courtesy of Chris Kugelman.

Early in his 25-year career as a photographer, videographer, and explorer, Chris Kugelman '94 worked an astonishing 14 months in the frigid cold of Antarctica for the National Science Foundation. There, he DJed for McMurdo Station, the logistics hub of the U.S. Antarctic Program, among his other duties. A nearby New Zealand base picked up the broadcast of everything from Beastie Boys to Johnny Cash.

As his audience grew, Kugelman upped the ante and changed formats, so he decided to make a film during his travels across the frozen continent. As he interacted with the explorers and scientists scattered across the frozen tundra documenting their work, he brought costumes and had the people read a handful of comical one-liners.

After filming all summer, he taught himself how to edit when everyone else was asleep. The day before the planes arrived to take people home, a sound system and projector were set up so everyone could view Kugelman’s first foray into filmmaking.

His production chops have certainly increased since he cut his teeth on that Antarctica video. He's collected a long list of credits at National Geographic and Red Bull Media House, and has been an executive producer on the awe-inspiring recent Disney+ series “Welcome to Earth” starring Will Smith.

It all started with a love of the outdoors, the first photography class he took at the Northern Virginia 4-H Educational Center, and his experiences in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Virginia Tech.

Kugelman traveled around Antarctica using Ski-Doos. Photo courtesy of Chris Kugelman.

To the Blue Ridge Mountains and beyond

As a kid, Kugelman was outside from sunrise to sunset. He explored his surroundings and caught insects, but what he wanted to do most of all was go camping.

His dream became a reality when he attended 4-H camp, which was held at Powell’s Fort, the old 4-H camp in Front Royal, Virginia, before it later moved to the Northern Virginia 4-H Educational Center.

With the help of John Dooley, the first director of the new 4-H center, Kugelman became a camp counselor at Camp Fantastic, a summer camp for children with or recovered from cancer.

Kugelman gravitated to the mountains of the New River Valley when it was time to go to college. He had seen Virginia Tech’s campus firsthand as a high schooler when he attended a Future Farmers of America camp on the Blacksburg campus.

“Virginia Tech had anything — and everything — I could be interested in doing,” said Kugelman, who earned a degree in human nutrition, foods, and exercise. “That helped show me that there was an entire world out there and that I could tackle whatever I wanted.

Those experiences came outside of the classroom, too.

He played club-level rugby all four years at Virginia Tech, and things got serious his sophomore year. Teammates that didn’t know each other came together. They started winning, first the regionals, and then mid-Atlantic. The Naval Academy stomped them in the finals. The same thing happened his junior year with another brutal defeat in the finals.

But his senior year, in a threepeat finals matchup, Virginia Tech won.

“That was four years of hard work,” Kugelman said. “It may not be academic work, but it was a club that was disciplined and worked hard to achieve a goal together. I feel proud of that.”

The foundation of classes and experiences that Kugelman had at Virginia Tech impacted him deeply and fed his personality. The hiking trails in the Blue Ridge Mountains and the intense mountain bike trails near campus helped Kugelman discover who he was as a person.

Chris Kugelman has a soft spot for Hamlet, an orangutan featured on the show "Orangutan Island" on which Kugelman worked in the mid-2000s. Photo courtesy of Chris Kugelman.

A small step into a larger world

Two years after he graduated in 1994, Kugelman worked at the National Science Foundation, when he experienced some of the toughest environments on Earth. He worked four summer seasons and one summer season in Antarctica and a six-month deployment in Greenland to support the research done by scientists and explorers.

It was also around that time that he truly got into photography. He bought his first real cameras — a Nikon FM 2 and a Cannon 50 SLR — and told himself he was going to be a National Geographic photographer.

He would carry the camera and rolls of slide film in temperatures of minus 50 degress in the dead of night to photograph the auroras. He had a special tripod made that could stand the wind so he could get the proper long exposures. He took more than 100 rolls of film with him on his excursions to Antarctica, which he couldn’t develop until he got back to Virginia. He’d often go six months without seeing a single frame.

“It’s not something people could even comprehend nowadays,” Kugelman said.

Antarctica was a deeply important chapter in his life, where he not only cut his teeth with professional photography, but also where he met his wife.

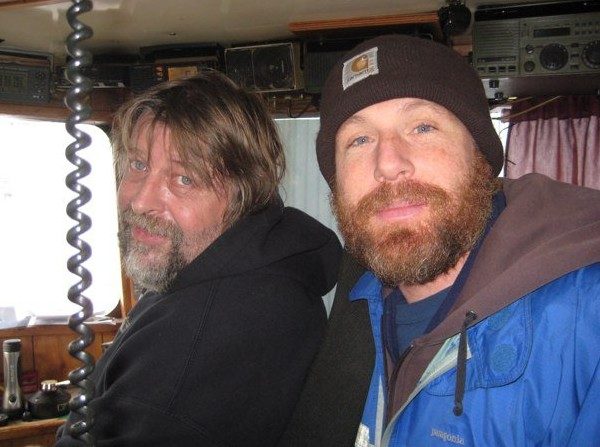

Capt. Phil headed the tourist icebreaker ship on which Kugelman, right, worked in Antarctica. Photo courtesy of Chris Kugelman.

A trip to Middle Earth

Before he left Antarctica, he took a job as expedition staff on a tourist icebreaker ship that took people around the continent so they could see penguins by helicopter. During that time, he started an application to a wildlife film school in New Zealand but didn’t complete it. He was self-taught and thought there was no way he would get in.

One day while on the boat, he got a call over the blower — slang for the ship's intercom — “Staff member, Chris Kugelman, please come to the bridge.” This was only for emergencies. Kugelman was terrified as he entered the bridge.

“It was my father,” Kugelman said. “He said that he wanted to congratulate me on getting into film school. ‘What?’ I said. I had never turned in the application. My father told me he had finished and submitted it for me.”

The program was run jointly by the University of Otago in New Zealand and Natural History New Zealand, now known as NSAID, which is the largest producer of documentary television and films in New Zealand.

In his final year in the program, he went back to Antarctica to film his student thesis project. Natural History New Zealand saw it and asked Kugelman to stick around. His experience in remote areas and harsh environments made him the perfect candidate for all kinds of polar or remote areas, such as Borneo.

“They found it useful putting someone in environments like that, so I found myself directing and producing a series for Animal Planet about orangutans,” Kugelman said.

This series led to another. Which led to another. And another. Pretty soon, Kugelman had built up a large body of professional credits.

Kugelman was part of the Discovery Channel's "Deadliest Catch" team that won an Emmy in 2011 for Outstanding Cinematography in a Reality Series. Photo courtesy of Chris Kugelman.

A goal years in the making

After five years of seeing the world, Kugelman moved back to Washington, D.C., where he fulfilled a lifelong goal: He was hired by National Geographic as a director and producer.

Red Bull Media House was his next step in the journey, where he made films about expeditions and actions sports — something the company is known for with its ventures in motorsports and other extreme sports. There, he made documentary TV series such as "Breaking the Day" and "Liquid Science."

An old friend reached out after a few years, asking him to come back to National Geographic, this time as an executive producer where he would help see the journey of a video project from an idea to the screen.

Reunited with National Geographic, he began work on one of the most ambitious projects he could recall in his 20-plus years in the industry: taking an A-list celebrity and placing him in some of the most dangerous locations on the entire planet.

On the Disney+ series “Welcome to Earth,” actor Will Smith ventured into a live volcano, crossed the Serengeti, and whitewater rafted glacier runoff in Iceland.

The scale of the production was astounding, Kugelman said. National Geographic, Disney, Darren Aronofsky, Protozoa Pictures, Westbrook Pictures, and Nutopia collaborated on the project of epic proportions.

“It was nothing short of mind-blowing,” Kugelman said. “We were trying to accomplish new types of photography and storytelling. I had to learn a lot. This was the hardest thing I’ve ever been associated with in my career.”

The teams had to figure out how to get production crews onto the tops of glaciers in Iceland, how to get them into the middle of the desert in Namibia, and how to work around a volcano that is actively shooting red-hot lava into the air that’s landing as rock.

For National Geographic, Kugelman listened to ideas for the story, pitched new ones, and helped keep the puzzle that comprises a film together.

“Film is an idea attached to pictures, with words and/or music to go with it, to push your story forward with a clear beginning, middle, and end,” he said. “I needed to make sure that what we were doing was effective in doing that.”

The challenges associated with filming over a 2 1/2-year span that included a global pandemic were worth it when Kugelman finally got to sit down and watch it with his son.

“He was enthralled. This is the proudest moment of my career. It’s what my journey was all about and I got to share the result with my son,” Kugelman said.

To this day, Kugelman is still interested in everything “because that’s the beauty of being in the natural world.”

“Every six months, I’m meeting some scientists or an explorer who is investigating the natural world or on an adventure that I am 100 percent interested in,” Kugelman said. “I'm fortunate to get to make projects with those folks, and I think that comes directly from my personality and the path I wove from 4-H to Virginia Tech and beyond.”

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)