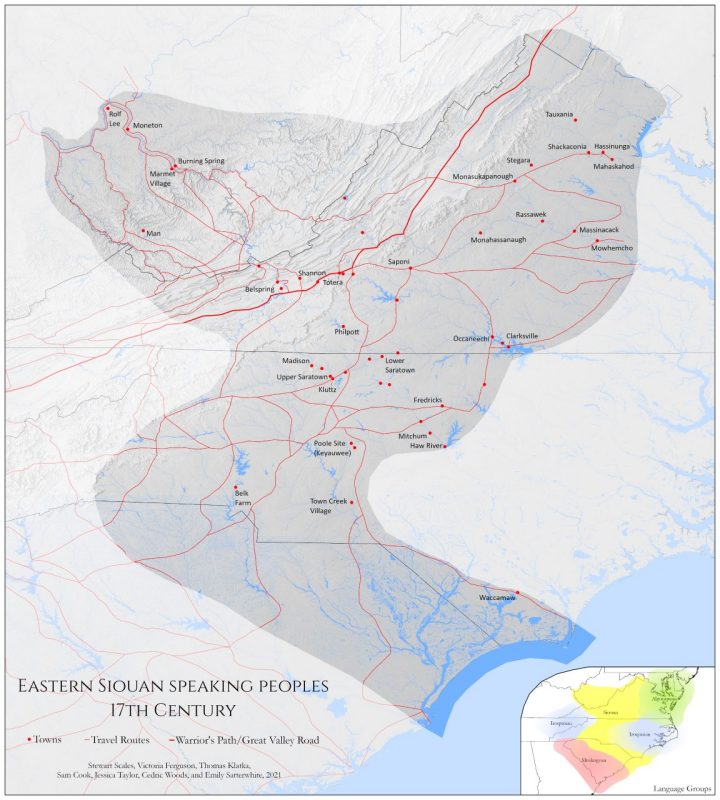

A new map reconstructs the social landscapes of Southwest Virginia prior to European arrival

The shape of the land is familiar, but the names on this map are different.

Gone are the names of capitals and cities and towns that are familiar to us: Richmond, Roanoke, Charlottesville, Raleigh. Absent, too, are the veins of the interstates and highways that trace the connections between those places.

In their place are older names: Rassawek and Monahassanaugh and Occaneechi. They are connected by older routes: a dark line passing between the Monongahela Forest and the Blue Ridge Mountains marks the Warrior’s Path, a critical travel route that ran along the Great Valley of Appalachia, on nearly the same place where I-81 currently sits. Other lines indicate trade routes for people who occupied the land long before European settlers arrived.

It is a map, but instead of depicting a territory, the darker shade that reaches from the Appalachian Mountains to the North Carolina coast depicts the estimated spread of the Eastern Siouan Language, offering a critical snapshot of a world that has been too-long forgotten in the collective history of the land where Virginia Tech is situated

The map was a collaborative project, bringing together the mapping skills of College of Natural Resources and Environment advanced instructor Stewart Scales with knowledge and input from professors, historians, and members of Virginia tribal communities, to create a tangible vision of what the region looked like prior to European colonization.

“The beautiful thing about maps is that they let us see the unseen,” said Scales, who teaches in the Department of Geography. “It’s very rare to see any remains from these civilizations or any markers of the trails they utilized, and, as a result, most people are unaware of how extensive the towns and areas of influence for Eastern Siouan Speaking Peoples in this region.”

Yesa: “The People”

“You’ll probably notice that we call the people represented on the map Yesa, not Monacan,” explains Victoria Ferguson, interim director of the American Indian and Indigenous Community Center at Virginia Tech and a member of the Monacan Indian Nation. “Yesa means ‘the people,’ and the term gathers all of the groups in our alliance, all of the Eastern Siouan speakers who lived in this region.”

The Eastern Siouan speakers, whose first recorded encounter with Europeans occurred when Christopher Newport’s expedition crossed the James River in 1608, would withdraw from much of the territory by century’s end to escape the encroachment of settlers.

To undertake a broad documentation of the trade routes and villages central to Eastern Siouan speaking peoples, Scales and Ferguson worked with Emily Satterwhite, associate professor and director of Appalachian Studies; Sam Cook, associate professor and director of American Indian Studies; and Assistant Professor Jessica Taylor, all in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences. Thomas Klatka, an archaeologist at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, also contributed crucial information about the distribution and villages for Eastern Siouan speakers on the land.

“This project originated as part of the Council on Virginia Tech History’s sesquicentennial commemoration plans,” Satterwhite explained. “We wanted to tell a deeper history of the land the college is on, and we realized that we didn’t have a good map that showed the university in relation to the nations that were here prior to colonization.”

To expand on that initial map that focused on the region around Virginia Tech’s campus, the group received funding from the Department of Religion and Culture, which gave them the opportunity to provide a broader vision of what the region looked like in the 17th century.

Making history tangible

The lines and places on the expanded map offer a view on what life was like in this region four centuries ago, as well as the critical ways that trade influenced interactions between various language groups.

“These peoples weren’t isolated,” said Cook, who teaches in the Department of History. “I hope that the map conveys that this continent was saturated with networks of trade and interaction for many years. These were communities that moved out of necessity, sometimes to preserve natural resources or because of the pressures of climate challenges from the Little Ice Age or later the pressures of colonization. This was a fluid moment, which can be difficult for us to grasp.”

And it was a moment of collaboration across shifting boundaries and politics.

“The term ‘alliance’ includes the fact that these Eastern Siouan speaking groups traded with one another,” Ferguson explained. “Their territories covered a lot of land, so natural resources trade was important. One example is that we don’t have good flint in this area, but we have greenstone, which was needed for making axes. Trade necessitates contact with one another.”

The names on the map note a variety of markers, from archeology sites where remnants of Eastern Siouan Speaking Peoples villages have been found, to natural resources like springs and rivers, to Rassawek, the historical capital of the Monacan Indian Nation. Once covered with bark houses, religious buildings, and burial plots, this site along the James River is considered sacred to the Monacan Indian Nation.

“Our history needs to go back further,” said Scales, who is himself a native of Appalachia. “The foundation was here long before Europeans arrived, and while that story is being told more, we still have a long way to go to completely understand what that element of our history demands of us now.”

A changing map to accommodate an emerging story

The story of Siouan speakers in the region is still being explored, and the map aims to reflect a history that will inevitably change as more is understood about the movements of Indigenous People in the region.

“I want to emphasize that this map is a work in progress, and it always will be,” said Cook. “It’s very difficult, especially for contemporary audiences used to modes of binary thinking, to understand that there weren’t absolute boundaries that defined territories. There were multicultural and multilingual settlements everywhere, and they endured through systems based on mutual understandings.”

Satterwhite notes that having a map of pre-colonial Virginia allows a richer understanding of the land where Virginia Tech sits, a perspective that is critical as the college celebrates the 150th year of its founding.

“Part of our hope for the sesquicentennial is to talk about the tri-racial contract zone that is Appalachia,” she noted. “That includes the Indigenous peoples who were already here, the Europeans who settled here, and the African slaves and freed people who were in the area. Having a map that centers the Eastern Siouan Speaking Peoples helps us tell a fuller story about Appalachia and the deep history of this land.”

For Ferguson, having a map that recognizes the spread of Eastern Siouan Speaking Peoples is a way to demonstrate a vast and complex world that merits remembering.

“For me, the importance of doing this is that people still don’t understand the depth of the Eastern Siouan speakers. Because the Monacan Nation is still here, you’ll hear about us all the time, but the reality is it wasn’t just our tribe that populated the interior portions of Virginia. There was a massive spread of tribes in the region, and their territory was huge. Being able to see that makes the history more tangible.”

And while the Eastern Siouan languages are some of an unknown number of languages lost, Ferguson stresses that the traditions and practices of the indigenous groups who shared this land centuries ago are still alive today.

“The aspect you have to think about for all indigenous peoples is what are the things that hold us together,” Ferguson continues. “We don’t have a reservation, but we have a community. We don’t have our language anymore, but we have idiosyncrasies in how we speak. We have traditions of gardening and gathering that have helped us survive. And we have family: because we’re in this tight-knit group our families are huge. All that factors into the community we are.”

Written by David Fleming