Curriculum grant fosters novel approach to teaching art history

Which artists are represented in the canon of modern art history? Has the art world fostered an incomplete view of the history of art and its makers? Annie Ronan, assistant professor of Art History, has been awarded a grant from the College of Architecture and Urban Studies to explore these questions as she revises the curriculum for a class on European and American art since 1900.

Ronan’s approach will help her students look beyond the traditional canon and understand how critical race studies, feminism, and queer studies have diversified our view of art history. They will explore the impact of colonialism and white supremacy on modernist practice and consider how inequities of power have shaped the study, collection, and display of art.

Teaching a large survey course at her previous institution prompted Ronan to seek help. She participated in “Teaching With Primary Sources,” a two-year workshop program jointly run by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, the Lunder Institute for American Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. There, she collaborated and experimented with art history faculty from multiple institutions to develop innovative ways of teaching. She brings those innovations to her work in revising the curriculum for “Art since 1900.”

Kathryn Clarke Albright, associate dean for academic affairs, and professor of architecture, developed the call for proposals to revise curriculum across all four schools in the College of Architecture and Urban Studies.

“Eleven curriculum grant proposals were funded, which is a tangible demonstration of our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion across the college,” Albright said.

Eight programs are represented by the grants: Studio Art, Art History, Building Construction, Urban Affairs and Planning, Center for Public Administration and Policy, Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Interior Design. Grant proposals address at least one of three broad focus areas: equity, access, and the human condition in one of the college’s disciplines; diversifying sources and case studies; and diversifying global perspectives.

Ronan said that receiving the grant empowered her to experiment on curriculum development with the “knowledge that my institution was behind me and supported my efforts completely.” With that support, Ronan emphasizes active learning strategies and discards exams and other assignments that place outsized importance on information recall. Her students are encouraged to express “their unique perspectives through low-stakes writing assignments, online/offline discussion, and other interpretive activities.” A key focus of the course is participation in a scaffolded research project that “helps students recognize and realize their capacity to rewrite the history of art.”

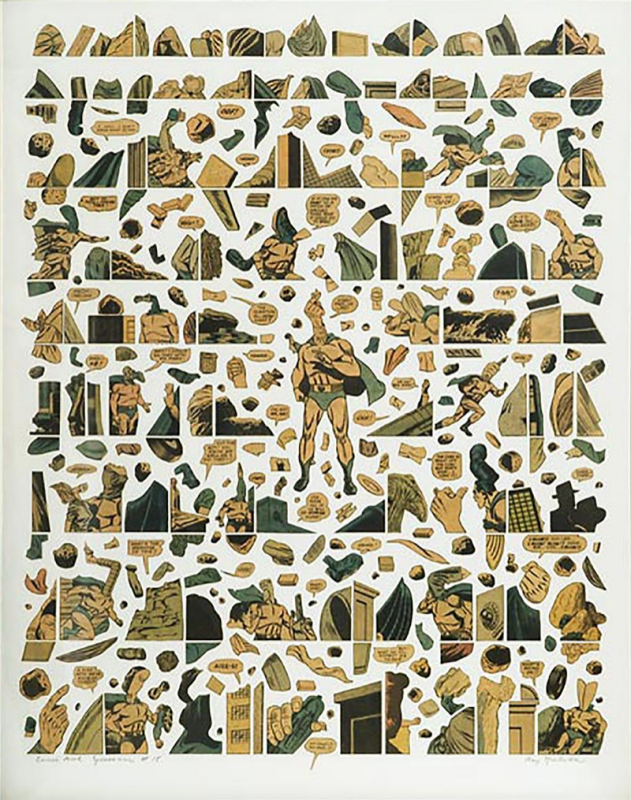

To meet these goals, Ronan developed the Curated Chronologies research project, which is intended for all levels of undergraduate students in art history. It is well suited to both in-person and online teaching formats. Students access “digitized collections of the Archives of American Art (and/or other institutions) to construct visually and textually rich art historical timelines.”

Building the timelines is an alternative to writing traditional research papers. Students work on a progression of short assignments that help them build skills and confidence to do their work in the digital archives. They use primary sources to complement their review of recent scholarly literature.

The Curated Chronologies website is the result of Ronan’s engagement with the Archives of American Art and brainstorming with academic colleagues. She worked with Virginia Tech’s Technology-Enhanced Learning and Online Strategies (TLOS) to build the website and put it into practice for undergraduate students. It provides an easy-to-use tool for building, publishing and sharing image-rich digital timelines.

Instead of producing a research paper, students become researchers. The timelines they create become a part of their professional portfolios. Students who create these interactive and visually appealing timelines that can be accessed from anywhere with an internet connection truly begin to stand out. Examples of completed curated chronologies can be found on the project’s homepage.

Written by Michael Capocelli