Finding a home with the Hoge family

Irving Peddrew III was accepted into Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1953, but it was being welcomed into a Blacksburg couple’s house on East Clay Street that helped him feel at home.

“Mrs. Hoge was a motherly type. She made sure I was comfortable,” said Peddrew, the university’s first Black student, during a phone interview in August. “She prepared all the meals, and I think did some of my laundry. They tried to make my life as homey as possible in their home.”

Born in the 1880s and the children of Black Americans who were likely once enslaved, Janie and William Hoge were about 66 and 70 years old, respectively, when they opened their home at 306 E. Clay Street to the first Black students allowed to attend Virginia Tech, then called Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

Though admitted to the university, the students could not live, eat, or otherwise use nonacademic amenities on campus. The Hoges provided them with not only room, board, and laundry assistance for $60 a month, but also a sense of care and support the students would have been hard-pressed to otherwise find.

“Mr. and Mrs. Hoge committed themselves to making our beds and cleaning our rooms each day, giving us three meals a day and washing and ironing our clothes,” wrote Lindsay Cherry, who joined Peddrew with two other Black students in 1954, in his memoir. “If there were heroes from the integration of VPI, it is these wonderful souls.”

In August, the Executive Committee of the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors recognized the essential role the Hoges played in facilitating the beginnings of Black students enrollment by voting to name the residence hall located at 570 Washington Street SW after the late couple.

“This naming will serve as a reminder of the unselfish care and dedication of Janie and William Hoge to a cause that continues to reverberate through the years since the first African-Americans enrolled at Virginia Tech,” the resolution reads in part.

The residence hall already houses Virginia Tech’s two engineering living-learning communities, which makes it a fitting tribute given it was the only subject the first Black American students could be admitted to the university to study as a result of the separate-but-equal laws of the time.

Most of what is known about the early lives of the Hoges is derived from U.S. census records. The 1930 record shows the couple living on Clay Street with one son, William, who was 13 at the time. It indicates the couple was married around 1907 and lists the father’s occupation as “farming.”

The 1940 census reveals more details about the family and the evolution of their lives on Clay Street. It lists the son as William H. Jr., then 22, as “adopted son.” It also shows the senior William completed school through the third grade and Janie through the seventh. A World War II draft card also indicated that the senior William was “crippled in the left foot due to a broken ankle – walks with limp.”

The Hoges’ occupations appear to have changed by 1940. In the census, William is listed as a “cement finisher” and Janie as a “chamber maid” for “Faculty Center, V.P.I.” Nine boarders, all documented as Black, are also listed as staying at the Hoge residence. The boarders included one family of three and at least two other university employees.

Boarder Fred Burley is listed as a tailor’s repairman in the pressing shop at VPI and Fred Caldwell as a barber in the college barber shop at VPI. Caldwell was still living with the Hoges in the 1950s, according to Virginia Tech’s first Black students.

“He and I got along pretty well,” said Peddrew, adding that he even spent his first Thanksgiving in Blacksburg with Caldwell’s family in Bristol, Tennessee.

It’s unclear exactly how the Hoges began boarding students. Peddrew said he didn’t know of them, nor that he would be living on Clay Street, until he arrived in Blacksburg.

“I thought I would be a part of student body all around. I didn’t know about all the restrictions,” he said. “But since I was there, I said, ‘Well, let’s make the best of it.’”

Peddrew said it makes sense, however, that the university would have known about and made arrangements with the Hoges, given their ties to university employees and the lack of housing opportunities for Black Americans in that era.

“Mostly when you hit an area like Blacksburg, a small rural town, you’d have to rely on someone you knew who could direct you to some place to stay,” Peddrew said. “It was quite a pain just to find a place to lay your body up for the night.”

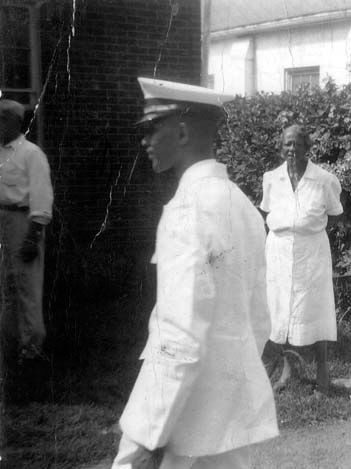

Longtime Montgomery County resident and Blacksburg barber Charles Johnson confirmed the Hoges’ reputation for boarding within the Black community. Following his service in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, Johnson returned to Blacksburg in 1956 and stayed alongside some of the students at the Hoges’ house for some time.

“Blacks just expected to be treated different, so when they [the Black students] came here, they didn’t expect it to be easy for them,” said Johnson. He specifically recalled the students not being allowed to attend a reception held by then-President Walter Newman.

“Instead, he [Newman] paid Mr. Hunter Bell $25 to drive them around town,” Johnson said.

The university’s lack of inclusion of its first Black students stood in stark contrast to that of the Hoges. Johnson remembers attending at least one welcome party they threw for new students.

“Mrs. Hoge was just like a mother to those kids. She got them up, got them ready, and made sure they got to school. Even got their uniforms cleaned,” Johnson said. “She liked to help people and that kind of thing. And old man Hoge, he did a lot of the cooking. It was more or less a family environment, for sure.”

Not allowed to eat or use other nonacademic university facilities, such as the students’ center, the students would trek through Blacksburg to and from the Hoges’ for lunch. They weren’t allowed to take part in campus traditions or social activities, such as the Ring Dance, and in the Town of Blacksburg, they weren’t allowed in any restaurants, drug stores, or barber shops, and they were restricted to the balcony if they wanted to see a movie at the Lyric Theatre.

But at 306 East Clay St., they were not only made to feel at home, but also connected with the region’s Black community. Charlie Yates, the university’s first Black graduate, described this effort to ensure the students didn’t feel isolated during a 2000 interview with the university.

“There was a special effort made because we essentially lived in that community. We became a part of that community,” said Yates '58, who was a member of the second class of Black students admitted in 1954. “We were students that came over to campus during the day, and once our studies were over, we were back as part of the community.”

Yates said there were definitely negatives to living off campus, such as having to change uniforms for events like parade or drill practice in other students’ rooms and struggling to connect with his white classmates to study or hang out. But living with the Hoges also provided the upside of direct access to the region’s Black community.

“If we were living on campus, we would not have had this, because living as cadets there were certain restrictions about when you can go and when you have to come back,” Yates said. “Really living in the community provided pretty much as a normal social life of an African American in the community at that time.”

This included traveling to visit Black communities in neighboring towns like Floyd, Radford, and Christiansburg, which was home to Southwest Virginia’s first high school for Black students, Christiansburg Industrial Institute. And it also included many short walks over to the First Baptist Church.

“There was church right next door to Mrs. Hoge’s house where we participated in church activities,” said Essex Finney, who transferred to VPI from Virginia State in 1956, in a 1999 interview with the unversity. “And I thought we had a very good social environment at Mrs. Hoge’s house with the other students.”

Cherry echoed Finney’s thoughts in a 1999 interview with the university.

“There was a very small Black community here,” said Cherry in comparison to his hometown, Norfolk. “I went to church often and sang in the choir over on Clay Street. People were very nice, though, a very quiet community. It was a different type of environment from that of the city, and I really enjoyed living up here in these hills.”

By all accounts, the Hoges continued to take care of Virginia Tech’s earliest Black students until Janie Hoge died in June 1960. William Hoge then relocated to Norfolk, where his son, William Harris Hoge Jr., then lived and worked for the city’s recreation department. He died four years later in 1964.

The Hoges didn’t live to see the legacy they helped start. They never saw the full impact of James Leslie Whitehurst ’63 breaking color barriers by both living on campus and attending the Ring Dance, nor the six Black female students admitted and allowed to live on campus in 1966.

But in the decades following the Hoges’ deaths, it would be become clear that their efforts to welcome Virginia Tech’s first Black students into their house helped pave the way for others to call the university home. It’s one of the primary motivations behind a call Cherry made in his memoir to see the family memorialized.

“When I say our cause, I am speaking not only of the six original Black cadets who were fortunate enough to spend valuable time with Mr. and Mrs. Hoge, but also the thousands of you who followed in our footsteps, it is important to realize that you too are recipients of their unselfish sacrifice,” Cherry wrote.

— Written by Travis Williams