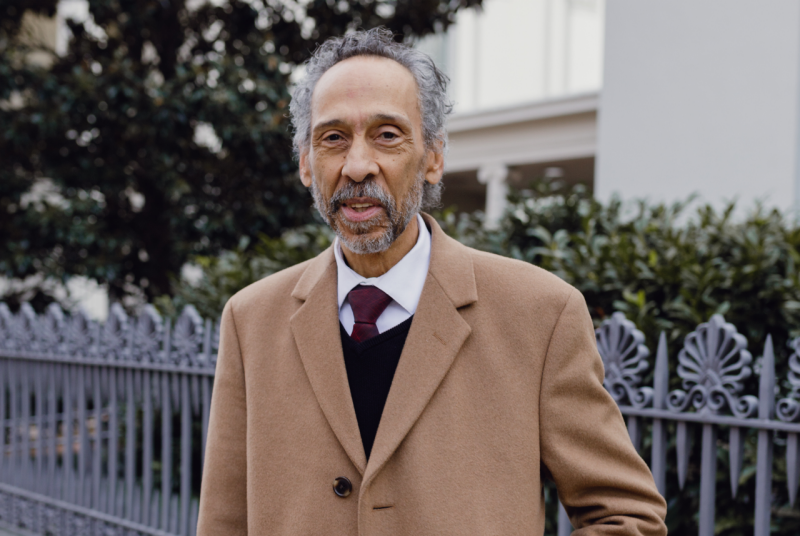

Virginia 4-H agent Hermon Maclin gives youth a voice for the digital age

4-H’ers write, film, and star in videos that take on critical issues of their time

At night in his room above Alberta Lunch, Hermon Maclin could always feel music underfoot. By day, his family’s restaurant in Brunswick County, Virginia, served barbeque sandwiches, hamburgers, and hot dogs to locals and highway travelers. After dinner, it took new form as a busy social venue.

“We stayed open until midnight, and people just partied in there all night long,” said Maclin of the place where he spent most of his childhood. “I’m supposed to be upstairs asleep, but I’m peeping through the venting in the floors, checking the music out and checking the people out."

Big, constant, and humming all around him, music has had the same presence in Maclin’s life ever since. His love of bass carried him through his adolescence during the civil rights movement in the 1960s. He spent more than 40 years playing in funk and reggae groups Trussel and the Tunji Band. Today, music still drives Maclin’s work as a Prince George County 4-H Extension agent. To Maclin, music and other forms of creative expression should be embraced as learning tools.

“It comes through you, through your heart, through your soul, through your voice,” he said. “That God-given talent to sing about the good stuff. It goes the other way, too. If you’re singing about evil stuff, that gets into the souls of people. Right on down. Either way, it’s so powerful."

Since 2014, Maclin has served as director of Virginia Youth Voices, a program that enables 4-H youth to tell their stories using video projects, including music videos, skits, and spoken-word poetry. The program aims to inspire youth to “create with a purpose,” said Maclin. His students write, film, and star in their own videos, engaging their peers with messages that help them confront issues like racism, abuse, depression, family instability, and addiction.

Maclin remembers how it felt to be a voiceless kid.

In September of 1964, when Maclin was in seventh grade, he and 16 other children from Brunswick County became the first Black students to attend Lawrence Elementary School. Alongside 21 African-American students that attended Brunswick High School that fall, Maclin and his classmates were the first in the county to act on behalf of public-school desegregation.

“We got off the bus, and they were lined up on the east side, chanting, ‘Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate!’” said Maclin. “And then came the rain of gravel and balled-up paper.”

The push for school desegregation came from Maclin’s father, Hermon Maclin Sr., a 4-H agent and local tobacco farmer. As soon as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had passed, Maclin Sr. moved swiftly to work with area families to register their children as new students at the county’s all-white schools.

Initially, the parents of about 100 children were interested, but threats of job loss whittled the number down to 38 students by September, after the local newspaper published the names and addresses of those that Maclin Sr. had signed up. “They weren’t going to back down,” Maclin said of the families of the remaining 38. “This was something we needed to do."

During school, Maclin developed a general strategy of passing through the halls unnoticed and unbristled. “Don’t say anything,” he would tell himself. “You’re here, you’ve made your point.”

After his first year at Lawrenceville Elementary, Maclin spent the summer of 1965 learning how to play bass. His cousin, Leroy Fleming, played saxophone in Washington, D.C., and needed someone to play the bass lines to accompany his horn lines when he practiced. He taught Maclin. The summer Maclin spent playing with his cousin “nailed it down,” he said of his early dream to become a musician.

Maclin’s summer of music made the next few years at school feel different. After entering Brunswick High School, he found that music helped him and other students begin to work through division. Talent shows and marching band put students together in creative collaboration.

“We were all in the talent show at school, and it was Black students, white students, everybody getting together and making music,” he said. “We got to know each other better.”

As a student at Virginia State University in the early 1970s, Maclin formed a group called Trussel with several music majors and they released a hit record, “Love Injection.” He moved on in the 1980s with a few members of Trussel to start a reggae group called the Tunji Band.

“We did songs that had a message of unity, peace, love,” said Maclin. “The songs that are near and dear to my heart, that I wanted to tell to the people — I added those to our repertoire.” Maclin continues to play with the Tunji Band. Most of his songs still aim to send listeners messages that unite them.

“You change or inspire who you can, one life at a time,” he said.

Maclin’s journey to creating Virginia Youth Voices began in 2009. That year, 4-H Extension specialist Kathleen Jamison came to Maclin, then running a 4-H music business club in Prince George County, with the opportunity to participate in Adobe Youth Voices, a nationwide program designed to help students tap into creativity and digital skills for impactful storytelling.

Maclin brought a handful of students to the program summit, including his son Josh, a member of the music business club. The group took on a project they eventually titled “Different,” a video in which students take turns talking about personal traits that once made them feel alone: the way they dress and speak, their family structures, their beliefs, their habits, their quirks, and their physical features. Each student then gives advice about seeing such traits as good things.

After “Different,” Maclin received Adobe’s Creative Educator Award. “This is what I want to do,” he remembers thinking at the time.

Maclin founded Virginia Youth Voices to continue producing creative projects with students in Prince George County. He enlisted Josh Maclin as a volunteer and later a program instructor. His students, ranging in age from 12 to 18, have created dozens of videos since then.

In the video “Breathe,” Youth Voices member Alexandra uses spoken word and dance to share a difficult personal story of coping with sexual abuse. In “Together,” a group of Black and white teens play basketball players confronting their racial biases.

In “Who You Really Are,” the camera focuses on the face of a single teen Youth Voices member, Sydnee, in front of a lake. “I just have one question for you,” she says in rhythmic spoken word. “Who are you? I don’t know about you, but I know about me. May never be a size three, more like a size 13. Is that alright? To love the pigment that I inherited. To love the skin that I was born in. To stretch my hands from coast to coast. To fill up every stage with my grin. To change the people. In big waves, in little waves.” She then stares into the camera and finishes her poem: “Look onward into the vastness and forgive it all, and show them who you really are.”

Josh Maclin, who now works as a professional photographer and videographer in addition to the time he puts into Virginia Youth Voices, said the creative process for the videos is just as important as the end product. The entire Youth Voices group will usually work together to formulate ideas and create a storyboard from video to video. That leads to honest conversation and allows the students to open up to one another as well as the youth watching their videos.

“You’re taking kids who wouldn’t necessarily ever communicate these ideas to anyone — if they do, they’re keeping it in-house, among close friends — and you’re giving these very intimate ideas and issues and situations a huge platform,” said Josh Maclin. “That’s where the power lies.”

Josh Maclin said his father is particularly suited for the job of helping kids bring out stories that need to be heard.

“The kids just tend to gravitate to him,” he said. “His style is incredibly different than anybody else’s I’ve ever witnessed and in education, period. It’s just who he is as a person.”

Written by Suzanne Irby