Visit the Smithsonian’s new infectious disease exhibit and find a Hokie alumna making science accessible

Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Why should people and animals be vaccinated? How does disease spread between animals and people? How does an outbreak become a pandemic? What can we do to prevent the spread of viruses, such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and influenza?

Answers to these questions can now be found in the same space where dinosaurs tower and whale moans bellow. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., opened its doors on May 18, 2018, to reveal a new line of viral defense: knowledge of how disease spreads, where disease fits within the larger picture of the environment, and our place in it.

The exhibit, called Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World, is designed to teach visitors how zoonotic diseases, or those typically infecting animals that spill over to humans, spread to become a global threat.

Outbreak features nine diseases that have spilled over from animals, including bats and rodents. Two of the diseases featured, Ebola and Nipah, have outbreaks that are occurring right now. The exhibit examines what we can do to stop these disease outbreaks from becoming pandemics. But understanding our individual role in stopping a disease outbreak can be difficult.

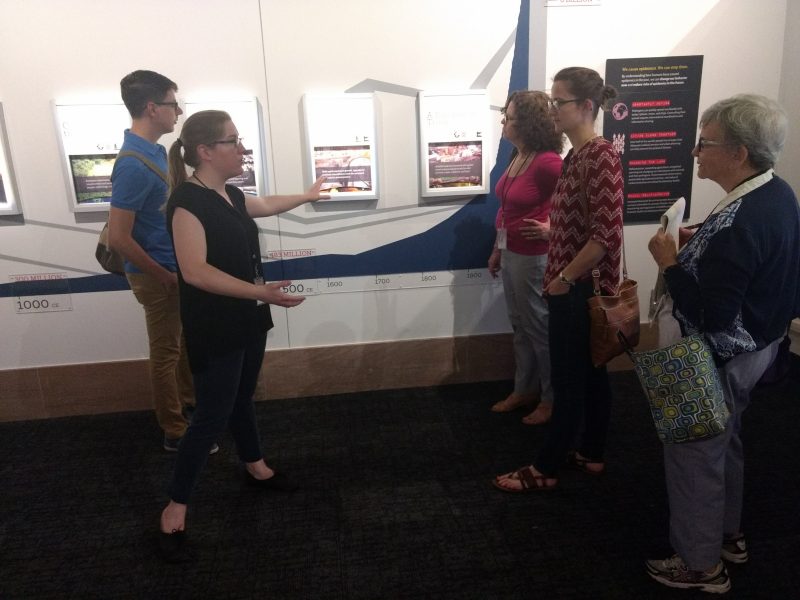

This is where Ashley Peery comes in. Peery, now a two-time alumna at Virginia Tech, spent the last six months developing materials to train volunteers for the exhibit. For six weeks from April through May, she led the training of 66 volunteers who live around the nation’s capital. The volunteers vary in age and expertise and include scientists, doctors, teachers, and science enthusiasts from the undergraduate level all the way up to retired professional.

“I find that the people recruited to volunteer in Outbreak are genuinely interested in learning how to share their knowledge with others,” said Peery, an American Society for Microbiology (ASM) fellow who is detailed to the Smithsonian as an educator.

Leading up to the exhibit’s opening, Peery was also responsible for developing activities and strategies that volunteers could use to help museum visitors connect with the exhibit’s messages about One Health, the idea that human health, animal health, and environmental health are all interconnected.

To develop the material, Peery pooled together resources based on her own expertise. At Virginia Tech, Peery first studied biology in the College of Science as an undergraduate, then as a doctoral student in entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. For her Ph.D., Peery studied genetic changes in Anopheles mosquitoes, which can carry malaria, under the guidance of Igor Sharakhov, an associate professor of entomology and an expert in genomics and cytogenetics of mosquitoes.

Peery also utilized the latest science and expertise from scientists working at the cutting edge of these fields. She drew material from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as from ASM’s network of experts. She created models that allow volunteers to engage visitors with specific examples of the roles of scientists and the public in the process, for example. Visitors are then asked how they would approach disease based on whether they wore the hat of an epidemiologist, a disease researcher, or a citizen concerned with infection.

The exhibit features nine zoonotic viruses: HIV/AIDS, influenza (both bird and human strains), hantavirus, Nipah, SARS, MERS, Ebola, and Zika. Each of these viruses tells a story of One Health and visitors learn the human, animal, and environmental components of each one. The exhibit also highlights an “upside” for each of the diseases.

“The One Health framework helps us understand how each featured disease has spilled over to humans, and shows how human actions can spread these diseases into outbreaks and even pandemics,” Peery said.

Factors that affect the spread of these viruses include habitat destruction, growing global populations, and domestication of animals, all of which the exhibit aims to explain.

“One Health is a holistic approach for thinking about disease,” Peery said.

The One Health perspective has been gaining traction over the past 10 years, Peery explained, but the concept has struggled to reach scientists working across the human, animal, and environmental forefronts of disease research. The exhibit will help bring this mode of thinking to light, Peery said.

The training course for Outbreak volunteers included online modules and face-to-face sessions. This in-person portion included talks by One Health experts from the CDC, USAID, ASM, and the National Zoo. It also included training in strategies for science communication and inquiry-based learning approaches.

The Smithsonian has well-developed methods for teaching volunteers, Peery explained. New volunteers are trained to consider their audience, speak without jargon, and use inquiry-based learning approaches as they interact with visitors. Outbreak volunteers take the role of a learning guide and use 3D models and guiding questions to assist visitors as they learn. In this approach, volunteers encourage visitors to take an active role in their own learning rather than simply providing answers.

“How do you leverage the information in the exhibit to reach specific learning outcomes so visitors walk away understanding the exhibit?” Peery asked, while developing the training materials in February 2018. “One goal of training is to equip Outbreak volunteers with a ‘bag of tricks,’ such as objects or ideas that visitors can relate to. This will help pull people in who are interested and build upon this connection so these folks leave with some deeper understanding of the exhibit.”

Peery will recruit and train new volunteers in early 2019 for those interested in joining the museum as volunteers.

In the future, Peery will also be working to promote DIY Outbreak, a print on demand version of the exhibit. DIY Outbreak is a 15-panel condensed version of the 4,400 square feet of panels, objects, and videos on view in the main exhibit. DIY Outbreak is available in other languages in addition to English—French, Spanish, Arabic, and traditional and simplified Chinese. It will serve as a flexible learning resource for people “who need a tool to educate their local community,” Peery said.

”My hope is that these very important messages of how diseases spread from animals to humans will reach communities around the world, not just those that are able to walk through the doors of the museum in Washington, D.C., and DIY Outbreak is really going to help with that,” Peery said.

This goal is fitting for Peery, who has continued to grow an interest in science outreach since her time at Virginia Tech.

When asked how Peery interacts with visitors who are skeptics, she noted, “You’re not going to change people’s minds, but we can reference the latest scientific data and meet them where they are. It’s really key that we meet the community where they are.”

The exhibit will run until May 2021 and is open year-round.

-Written by Cassandra Hockman