Virginia Tech Fulbright scholar partners with Uruguay to boost beef exports

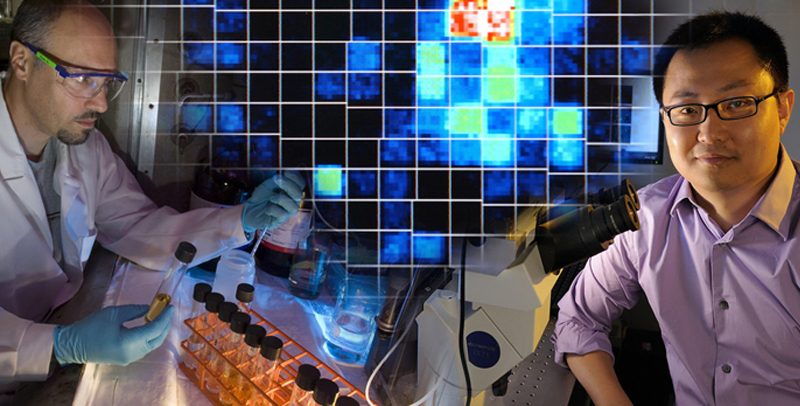

David Gerrard (left) and Alan Grant stand in front of the entrance to the Mario A. Cassinoni Experimental Station at the University of the Republic, Paysandu.

Roughly the size of a thumbprint stamped between its more capacious neighbors Argentina and Brazil, Uruguay holds distinction as one of South America’s smallest countries. But the country’s motto, “Libertad o Muerte” — Liberty or Death — speaks to the spirit and determination of its 3.4 million people.

Uruguay’s 98.1 percent literacy rate, one of highest in the world, is a result of the country’s free, compulsory education. With its lush and varied topography, temperate climate, proud cultural traditions, and robust economy, this South American agricultural powerhouse is positioned to become one of the continent’s key players in the global marketplace.

David Gerrard, head of the Department of Animal and Poultry Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Virginia Tech is keen to see this success continue. The Fulbright scholar recently returned from a five-week trip to Uruguay funded by his fellowship.

Gerrard’s Virginia Tech research program examines meat production, from the basics of muscle growth and development to the biochemistry involved in the transformation of muscle into meat, to studies involving technology transfer to monitor the quality of fresh meat. Of particular interest to the researcher is Uruguay’s ability to generate $1.5 billion in revenue from beef exports annually, nudging it just ahead of Australia as the second-largest exporter of beef to China.

A view of downtown Montevideo, overlooking the president's house and the headquarters of the National Institute of Agricultural Research. Grant and Gerrard met with officials at the institute while staying in the capital city.

“South Americans represent potential for a future in which there are 9.7 billion people to feed across the globe,” Gerrard said. “It may be time to graduate from thinking the U.S. alone will feed the world.”

In Uruguay, Gerrard sees an ideological affinity when it comes to agricultural methodologies as well as receptivity among decision-makers and producers to sharing new ideas and methods. The Fulbright award provided an opportunity to explore how Virginia Tech could play a role in helping to sustain a growing global population.

Gerrard’s Fulbright offers a two-year joint teaching/research scholarship, enabling him to divide his visits between teaching classes on meat science to students at the University of the Republic, the nation’s public university, and collaborating with university colleagues, producers, and officials within the National Institute of Agricultural Research, known as INIA, the nation’s primary food and agricultural governing body. The goal of the collaboration is to improve quality while also preserving grasslands, safeguarding animal welfare, and diversifying beef exports.

“One of their biggest concerns is retaining and growing their share of the beef export market, since about 80 percent of their beef is exported,” said Gerrard, noting that most Uruguayan cattle are grass-fed. “They realize grain-fed cattle have a following across the globe, in part based on the huge successes of U.S. and Australian beef in the world marketplace, especially in Asia.

"Grass and corn impart different characteristics,” he explained. “American corn-fed beef is perceived as more tender and is lighter in color.” To this end, Gerrard is researching the difference between pastured and corn-fed meat.

Gauchos are an important part of Uruguay's agricultural system.

Uruguay has met challenges with considerable innovation to date. Following an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in 2001, the country developed sophisticated supply chain tracking technology that equips authorities with the ability to track the movements of cattle throughout their life spans, maintaining accountability, traceability, and transparency.

The nation also launched the Certified Natural Meat Program, a protocol administered by the Instituto Nacional de Carnes, Uruguay’s meat export federation, outlining sanitation quality, environmental standards, and other guidelines forbidding the use of antibiotics and growth hormones. The pastured product is marketed under the “Uruguay Certified Natural” banner.

Yet, despite building a successful niche market for grass-fed beef, many ranchers want to adapt their product to the tastes and demands of new international buyers who seek a more tender, higher-quality product, according to Gerrard — a need perfectly aligned with the researcher’s background and interests. He views the Fulbright as a vehicle to establish a long-term collaborative relationship with Uruguay, a sentiment shared by Alan Grant, dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

During his first trip to Uruguay this year, Gerrard invited Grant to teach a class titled Animal Growth and Development to students at the University of the Republic at the school’s Paysandu campus in western Uruguay. The two met at Purdue University over two decades ago and co-authored one of the preeminent textbooks in the field of animal growth and development.

“I was interested in learning more about potential collaborations,” said Grant, who expressed excitement about the opportunity to learn from the Uruguayans about differences in the agricultural production systems. “After learning more about the country’s agriculture and its abundance of forage and grasslands, you can readily understand why they manage and feed cattle the way they do. Comparing and contrasting the two systems gives us a model to help understand the science behind the growth of cattle and the development of meat quality.”

Grant and Gerrard, center, enjoy dinner with friends at a home in Uruguay.

After a seven-year absence from classroom teaching, Grant was also pleased to return to the classroom. With some creativity and adaptation, he and Gerrard were able to teach nearly a semester’s worth of material in three long days.

The lectures were translated by Santiago Luzardo, a National Institute of Agricultural Research meat and wool expert and Colorado State University graduate who served as a host and interpreter to both Virginia Tech professors. Luzardo also helped introduce the visitors to the culture and cuisine of his homeland.

In Uruguay, meat is the most conspicuous item on nearly every restaurant menu. At restaurants and in homes, it is revered as the centerpiece of each meal — a plus for Gerrard.

“It was great,” said Gerrard who relished being in a country where cattle outnumber humans by 4:1. While Grant also took advantage of the dominance of meat on the menu; he especially enjoyed the opportunity to compare and contrast how meat is prepared in the two countries. Uruguay recently overtook Argentina as the beef consumption capital of the world. Four years after earning this honor, the nation’s crowning carnivore status remains a source of great pride to its people.

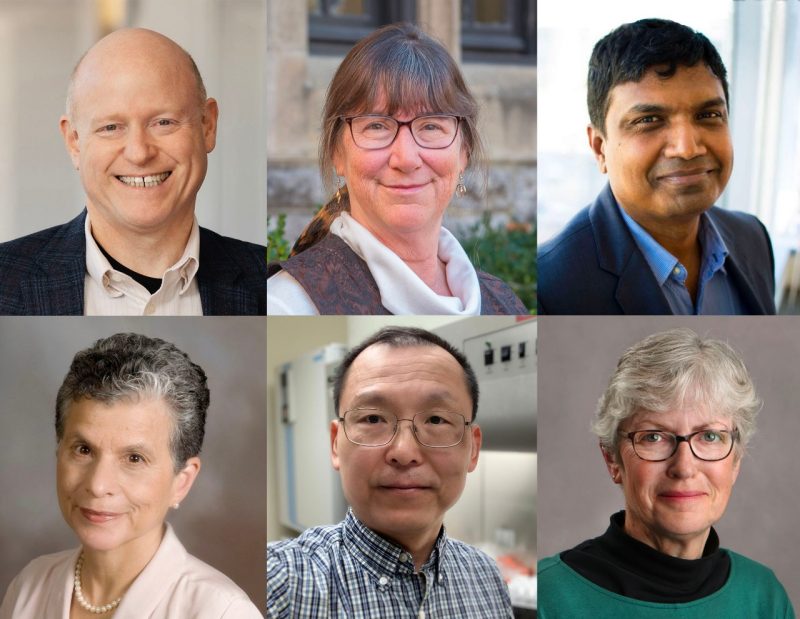

Gerrard and Grant (back row) pose with their animal growth and development students at the University of the Republic at the school’s Paysandu campus.

Gerrard will return in the spring for the second chapter of his Fulbright term. To date, he has taken in much of the country, particularly Uruguay’s ample grasslands, rolling hills, and Hereford ranches, traveling approximately 4,000 miles to meet with humans and herds alike.

“The longer you are there, the more everything makes sense,” he said. “I went to many people’s homes. They were very cordial and gracious hosts.”

The College’s Office of Global Programs is developing a memorandum of understanding with National Institute of Agricultural Research officials and the University of the Republic that will outline plans for graduate student exchange and research collaboration.

“Anytime you have graduate students going back and forth, it leads to collaborative opportunities for faculty,” said Grant. “Everyone has a piece to contribute. It’s a win-win.”

- Written by Amy Painter