Sub-Saharan African countries feeding themselves after years of improving crop varieties, studies find

The refrain "feed the world" in the 1980s anthem “Do They Know It’s Christmas” was a call to action to fight the devastating food insecurity problems that plagued Africa.

But a recently published series of studies on the adoption and impact of modern crop varieties in Sub-Saharan Africa provides reason for cautious optimism about the region’s future.

In regions of Africa, agricultural productivity is increasing and people are thriving. Overall, the prevalence of hunger declined by 30 percent between the early 1990s and 2015, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Investments in agricultural research are helping to alleviate crippling food shortages that racked the continent in the 1980s and '90s.

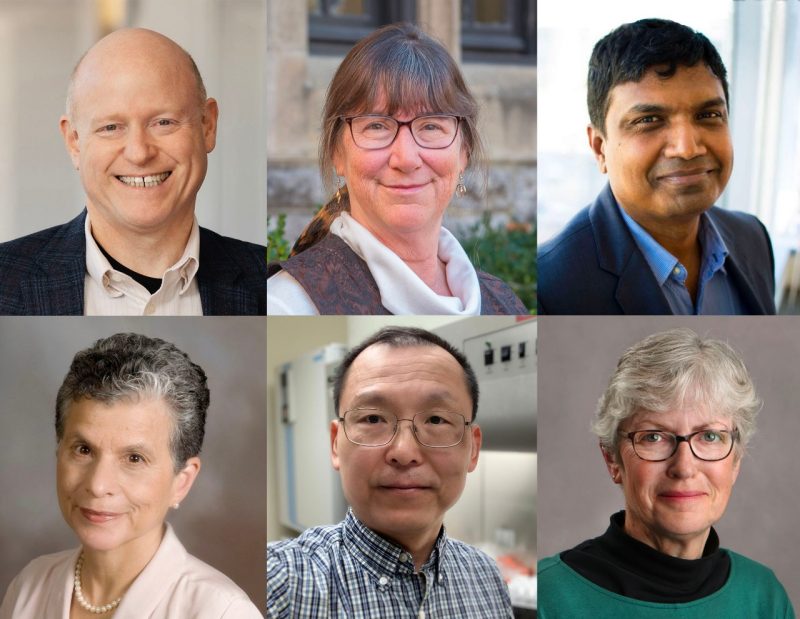

“We really don’t hear enough about the successes in Africa,” said Jeff Alwang, a professor of agricultural and applied economics in the Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences who edited the book. “These studies show the power of modern science applied to African agriculture. Science is helping African people feed themselves.”

The collection, titled “Crop Improvement, Adoption and Impact of Improved Varieties in Food Crops in Sub-Saharan Africa,” represents the culmination of a three-year project involving numerous international and African scientists to document the spread and impacts of improved crop varieties. Investments in agricultural research are alleviating crippling food shortages that racked the continent in the '80s and '90s.

In recent years, Alwang partnered with the International Center for Tropical Agriculture to assess the household and market-level impacts of iron-fortified beans in the Rwanda.

“We’ve heard a lot in the popular press about economic stagnation, political failures, and endless poverty and starvation in Sub-Saharan Africa. We hear much less about development successes such as alleviation of the AIDS crisis, major victories in the battle against malaria, improvements in education and other infrastructure, and an improved outlook for agriculture,” he said.

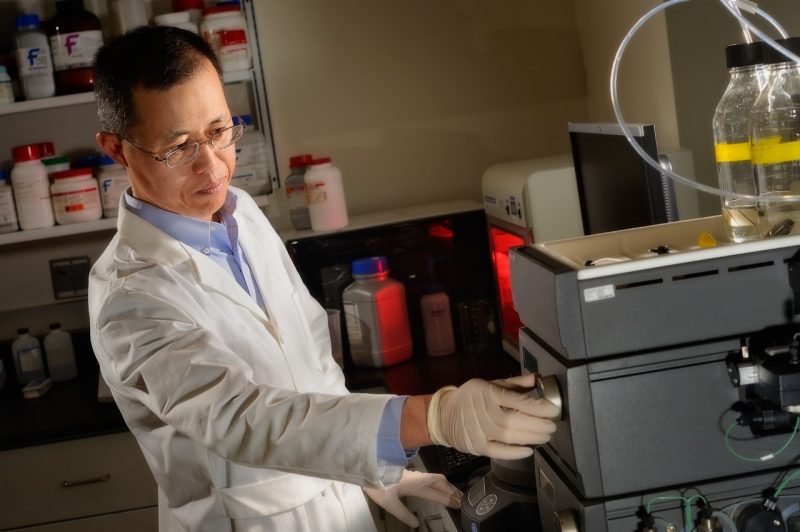

Alwang and other researchers from across Virginia Tech have been working in Africa for years to increase crop productivity, using everything from conservation agriculture to pest management techniques to developing economic models to maximize profit at the markets where goods are sold.

“We need to hear about how methods, such as crop improvement, are improving conditions in the region as well, because the truth is, there are food security successes in crop production happening. This is not to minimize continuing challenges such as low soil fertility, widespread pest problems, and increased drought and water stress, but most professionals are cautiously optimistic about the future of African agriculture,” Alwang said.

A few examples of successes are examined Alwang’s chapters on Ethiopia and Rwanda. These chapters were co-authored by Di Zeng, a former doctoral student in agricultural and applied economics; Catherine Larochelle, an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics; and Professor George Norton, also in the department. These sections also drew on researchers from international agricultural research centers and national agricultural research institutes.

Diffusion of improved crop varieties has been key to making Ethiopia more prosperous, and a stark contrast to the harsh rule of Haile Selassie that saw mass starvation in the country from 1972 to 1974.

Ethiopia’s improved crop varieties have contributed to improved food security and lower poverty. Over the last four decades more than 40 improved varieties have been developed and released in Ethiopia, doubling the calorie and protein contributions of maize to around 20 percent and 16 percent respectively.

As recently as 2010, 1.6 to 2.7 percent of the rural poor in Ethiopia escaped poverty due to the diffusion of improved maize, a percentage that translates to between 48,000 and 96,000 households that are no longer classified as poor.

In Rwanda, adopting improved bean varieties increased the average yield gain 53 percent over local varieties and reduced food insecurity by as much as 16 percentage points.

Rwandan households planting improved bean varieties gained, on average, an extra 42 kilograms of the crop over local varieties per agricultural season, increasing household revenue by U.S. $50, a large sum to small-scale farmers. This relatively modest boost to household income allows families to set aside extra money to send children to school, acquire land, and plant more crops.

In Uganda, Rwanda’s close neighbor, the yield gain due to modern bean varieties was 60 percent, translating to a 2 percent reduction in household food insecurity.

The findings of this series of studies paint a very different picture than the images of despair often associated with the African continent.

The volume, published by the Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers and the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International, highlights several achievements since 2008. The current collection was born out of the Diffusion and Impact of Improved Varieties in Africa collectively known as the DIIVA project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, which measured performance indicators of crop genetic improvement, collecting nationally representative survey data on varietal adoption, and assessing the impact of varietal change. The DIIVA Project covered 20 crops and 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“What this series of studies demonstrates is that increasing the use of modern varieties of major food crops leads to higher yields. This all means that African agriculture is feeding more and more people over time,” Alwang said. “People need to know that long-term investments in agricultural research and development are paying dividends. As agricultural productivity grows, incomes will grow, and these improvements will benefit the entire world.”

Written by Amy Loeffler.