Demand is rising for Virginia Tech's Communicating Science course

Virginia Tech graduate students Matthew D’Aria, from Richmond, Virginia, and Jackson Means, from Keswick, Virginia, faced each other, knees slightly bent, arms outstretched as though holding an immense blubbery weight. Each watched the other intently, mirroring the slightest move.

Means, a doctoral student entomology, led, spinning the tale of Murphy, a malevolent, obese dinosaur stuck in a volcano cone. D’Aria, a master’s degree student in human nutrition, food and exercise, echoed Means’ words so closely they almost spoke in unison.

Classmates turned toward the pair, abandoning their own assignments. All sound faded, save Means’ and D’Aria’s once-upon-a-time voices. When the story ended – the volcano blew out the other side of the planet, the temperature changed and the dinosaur did not fare well. Classmates murmured appreciatively.

The two graduate students were part of Communicating Science, a Graduate School course modeled on the work of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in New York. The mirror exercise may look and feel like play, but it is used by theater students and professionals to sharpen concentration, listening and reaction skills while developing trust and teamwork.

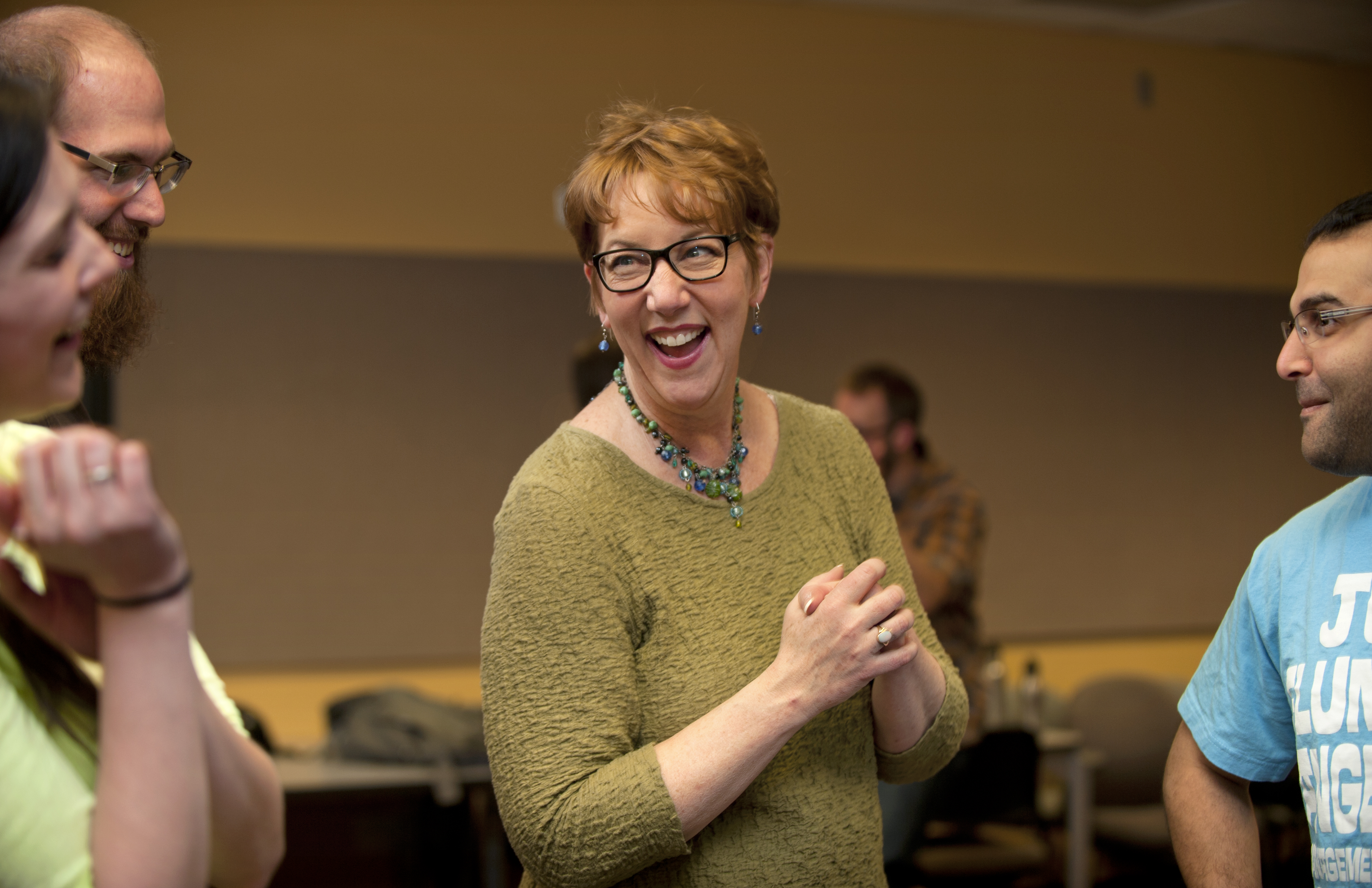

Those are among the skills scientists, scholars and teachers need to build relationships and connect with people outside their fields, and with the public, said Patricia Raun, a long-time actor and director of the School of Performing Arts at Virginia Tech who teaches the course.

Raun said the goal is for students to talk about their work with people who are not scientists, but the objective goes beyond translating jargon. Raun said the students learn the importance of conveying their passion for their work, and using narrative and storytelling to convey meaning. “They have to help me see the story in the data.”

The class was developed after Karen P. DePauw, vice president and dean for graduate education, attended a 2010 lecture at which Alda gave a presentation about his center. DePauw approached Raun and Sue Ott Rowland, then the dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, about creating a class for graduate students.

DePauw said graduate students in science, technology and other fields, whether preparing for a career in academe or in another professional field, must be able to share their work effectively and clearly with different audiences.

“Through the Communicating Science course and others we will engage graduate students with the university’s social responsibility to communicate science,” she said.

Raun, who trained with the Alda Center, had taught an introduction to acting class for non-majors for more than two decades at Tech that used similar acting exercises. She said students quickly learn that communications is about more than discussing work with colleagues or giving presentations.

“We’re at a crucial time in science,” Raun said. “The most important questions facing us now in science are ethical questions,” she said. “If the scientists can’t explain the importance of their work to everyday people we’re all in trouble. If it is possible for others to manipulate the message to their own advantage, they will. Scientists have to take the story into our own hands.”

Students in the spring semester class agreed. “I want to get people interested in my research so they understand,” said Kristin McElligott, from Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, a doctoral student in forest resources. “There is a disconnect between scientists and the stakeholders. Learning how to speak to people of diverse backgrounds about your research is important. You have to effectively communicate the problem.”

D’Aria said he wanted to take the course because he gets so excited about his field, he loses his train of thought. The exercises are helping him focus on his message while engaging with others. “The beautiful thing about this is it hits both sides: the big picture and the small details and how you connect them.”

No one sits in desks during the weekly seminar. Instead, they build their communications and connection skills with exercises, improvisations, impromptu conversation and discussion.

“This class is entirely participatory,” said biologist and writer Carolyn Kroehler, who began teaching with Raun in 2013 to focus on the course’s writing components. “They learn through group discussions, by throwing themselves into a mix of people who are not in their area, and through full engagement with all the improv and writing exercises.”

Means, who wants to teach at the university level, noted one class exercise in which students had to strike up a conversation with someone they did not know. Students talked with people on elevators, at bus stops, on a ski lift, in the grocery store or in the hallway of their lab buildings. “It’s interesting to train yourself to talk to strangers on the street,” he said.

The course also emphasizes active listening, Kroehler said. “They start out asking, how do I get people to listen to me? They finish the semester, we hope, understanding how important it is for them to listen to others and have developed the skills to do so.”

Raun said the class also builds relationships among the students. And she said the changes in the students’ interactions over the course of the semester are marked. “It is so important and it is something I can see.”

In a response to demand for the course, which always has a wait list of students who want to enroll, the Graduate School is adding more Communicating Science course sections for 2015-16, offering one in the fall and two in the spring.

Raun, who also gives Communicating Science workshops to departments and programs, said she hopes the university can develop “a web of communicating science” opportunities. “There is no end to the opportunities to expand,” she said. There is a huge hunger for it.”

Dedicated to its motto, Ut Prosim (That I May Serve), Virginia Tech takes a hands-on, engaging approach to education, preparing scholars to be leaders in their fields and communities. As the commonwealth’s most comprehensive university and its leading research institution, Virginia Tech offers 240 undergraduate and graduate degree programs to more than 31,000 students and manages a research portfolio of $513 million. The university fulfills its land-grant mission of transforming knowledge to practice through technological leadership and by fueling economic growth and job creation locally, regionally, and across Virginia.